India’s Trade Deficit With China: Stats Provide Grim Picture

India’s exports to China have risen and imports have fallen over the last few years. But a closer look at the items traded between the two countries shows the unequal bilateral trade.

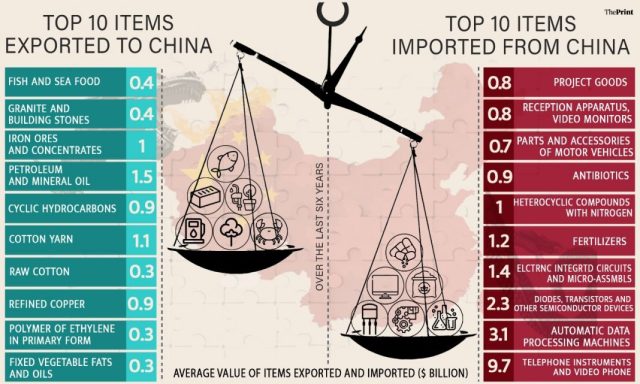

Trade numbers between 2014-15 and 2019-20 show that export of low-value raw materials and import of high-value manufactured goods has characterised India’s trade relationship with China, akin to the ties the country had with its colonial ruler Britain in the years before Independence, said trade experts.

This “colonial pattern” of trade has meant that India’s exports to China over the last six years have been only fifth in value of India’s imports from China.

While average exports from China have been around $13 billion in the six years ending 2019-20, the average value of imports from China has been $66 billion in the period.

India’s exports have ranged from food items like fish and spices to essential inputs like iron ores, granite stones, and petroleum products. Its imports from China have been dominated by electrical machinery and equipment, and other mechanical appliances.

Trade experts point out that this pattern is unlikely to change drastically in the near future and some of the changes seen in the current fiscal due to Covid may be short lived.

India’s exports to China

India’s major exports to China in the last six years were iron ore, petroleum fuels, organic chemicals, refined copper and cotton yarn. Among food items, some of the other major items exported were fish and seafood, pepper and vegetable oils and fats. Blocks of granite and other building stones and raw cotton were also among exports.

There have been some visible changes in the last few years based on changing tariffs and other factors in both the countries.

For one, the edge India had in export of copper cathodes has also been lost. Over the last couple of years, India has turned into a net importer of refined copper from being one of the largest exporters of copper cathodes to China.

Both its cotton and cotton yarn exports have also slumped in the last year.

What India imported over last 6 years

In contrast, India’s major imports from China have been of items like automatic data processing machines and units, telephone equipment and video phones, electronic circuits, transistors and semiconductor devices, antibiotics, heterocyclic compounds including nitrogen, fertilisers, sound recording devices and TV cameras, automobile components and accessories and project goods.

The current trade patterns reflect India’s manufacturing capabilities, said Ajay Sahai, director general and chief executive officer, Federation of Indian Export Organisation.

“It has something to do with the manufacturing capabilities of India. We import finished products from China to meet our domestic requirements. For instance, the telecom revolution in India saw major imports of telecom equipment and mobile phones in large quantities from China. China dominates the electronic hardware market while the Indian industry is still at a nascent stage,” he said.

However, he pointed out that with more companies manufacturing mobile phones in India, the country’s mobile import bill has come down.

“While we still majorly export raw materials to China, over a period of time India is gaining strength in value added exports. Our exports of cancer drugs, auto components and processed foods is picking up,” he said.

He also cited the example of cotton. Earlier, India used to export raw cotton and import cotton yarn, but is now instead exporting cotton yarn. “But this was mainly on account of China deciding to move away from labour intensive industries to medium and high technology industries,” he said.

The colonial pattern of trade

Noted historian Bipan Chandra wrote about the popular drain theory in pre-independent India, which was the basis of early nationalism. Among other things, it flagged how a free trade policy followed by the British in India saw an excess of exports of raw materials from India but without any improvement in the corresponding economic prospects.

In his book India’s Struggle for Independence, Chandra wrote how the essence of 19th century colonialism lay in the transformation of India into a supplier of foodstuffs and raw materials to the British, a market for British manufacturers and a field for the investment of British capital.

India’s exports during these times were of raw cotton, indigo, opium, jute, tea and raw skin and hides, while imports were of items like cotton yarn and iron and steel products. Unsurprisingly, Britain was India’s largest trade partner during this period.

Trade economists point out that the pattern of trade between India and China reflects this colonial relationship.

“The pattern of trade between India and China is a colonial pattern of trade,” said Biswajit Dhar, professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi.

“Whatever limited manufacturing capabilities were there in India eroded as Indian industry couldn’t stand up to competition from China. China being the factory of the world needed the raw materials and low level of intermediate inputs to fuel its manufacturing push. And India became a supplier of these inputs,” said Dhar.

Apart from India, Australia is another country from where China imports a large amount of its input requirement, said Dhar.

He added that one will have to wait and watch to see if schemes like production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes announced by the Narendra Modi government will have a significant impact in bolstering Indian manufacturing and reducing India’s dependence on China.

Dhar also pointed out that in 2020-21, in the aftermath of the pandemic, there has been some change in trading patterns but expressed doubt whether they will be sustainable in the long run.

For instance, India’s exports of semi-finished steel products to China saw a sharp surge in the months after the pandemic. This came as China’s manufacturing bounced back the fastest compared to other countries seeing a sharp rise in demand for steel products. With demand in India non-existent due to the pandemic, domestic steel companies started exporting.

But once domestic demand picked up, steel companies mainly sold in local markets rather than exporting.

Sahai, however, was optimistic. He pointed out that the PLI scheme could see India hone its manufacturing capabilities with cutting edge technology, and this could see the import bill come down.

Source: ThePrint, All the stats provided on ThePrint website.

Note: The accuracy of statistical information is out of the preview of IADN.